Current Distribution Rangewide

Restricted to California, from the Central Valley south to San Diego and northwestern Baja California, Mexico, at lower elevations [1].

Known Populations in San Diego County

Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton to the north and south to the Tijuana Estuary National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) along the international border [2, 3]. Within the MSPA they are known from MUs1, 3, 4, 5,6, 9, 10, and 11 [3].

List Status

CSC/FSC (Candidate for Federal Listing, Under Review) [4].

Habitat Affinities

Spend most of their time underground in burrows but require water for breeding [5]. They prefer open areas with gravelly, friable, or sandy soils in washes and vernal pools in the vicinity of grasslands, oak woodlands, coastal sage scrub, and chaparral [6]. Adults and juveniles use their hind legs dig burrows up to 0.9 m (3 ft) deep where they remain for up to 10 months [6,1]. They emerge after rain at night to forage and breed only a few nights a year. They breed in ephemeral wetlands such as vernal pools and stock tanks, but occasionally breed in intermittent streams where larvae develop in isolated areas of the stream as it dries [7,5]. Water temperatures in breeding pools must be between 9° C (48° F) and 30° Celsius (86° F) for reproduction and not contain exotic species such as American bullfrogs (Rana catesbeianus) and crayfish (Order Decapoda) [1]. Breeding pools are typically 18-24 in (20–60 cm) deep and hold water long enough for eggs to hatch and tadpoles to transform (approx. 30 days), completing their life cycle in 4-11 weeks [6, 8]. They are found at elevations below 365 m (1,000 ft), but they have been observed as high as 1,365 m (4,500 ft) in the mountains of San Diego County [5].

Taxonomy and Genetics

Member of the family Scaphiopodidae and was described by Baird in 1859 [6,1]. The family Scaphiopodidae includes two closely related genera of spadefoot toads: Scaphiopus and Spea [1]. Spea hammondii was once thought to have a much greater range, however differences in morphology, vocalizations and reproduction were detected between species west of Arizona and the populations to the east; California populations retained the name Spea hammondii (western spadefoot toad), eastern populations were designated as Spea multiplicata (southern spadefoot toad) [5,1]. Southern spadefoot toads are brownish above, have copper-colored irises and have a more elongate spade [1]. The species most similar to Spea hammondii are Spea couchii (Couch’s spadefoot) and the Spea intermontana (Great Basin spadefoot) [6]. They can be distinguished by the lack of a ridge between the eyes [1]. Spadefoot toads are distinguished from the true toads (family Bufonidae) by their vertical pupils, the spade on each hind foot, teeth in the upper jaw, and fairly smooth skin [9].

Seasonal Activity

Spadefoot toads emerge from burrows to forage and breed following rains in the winter and spring [1].Sound or vibration from rain drops hitting the ground appears to be an important emergence cue, and even the vibrations from walking near burrows can cause toads to emerge. One to only a few days after heavy rains (Jan-May), spadefoot toads congregate in breeding pools to attract females [6]. Females lay cylindrical eggs masses containing 10-42 eggs; they can lay up to 500 eggs in one with under suitable conditions [1]. Egg masses are attached to underwater vegetation where males fertilize them externally after amplexus [2]. Breeding pools are usually turbid with little cover and must reach suitable water temperatures before eggs are laid and fertilized [5].

Life History/Reproduction

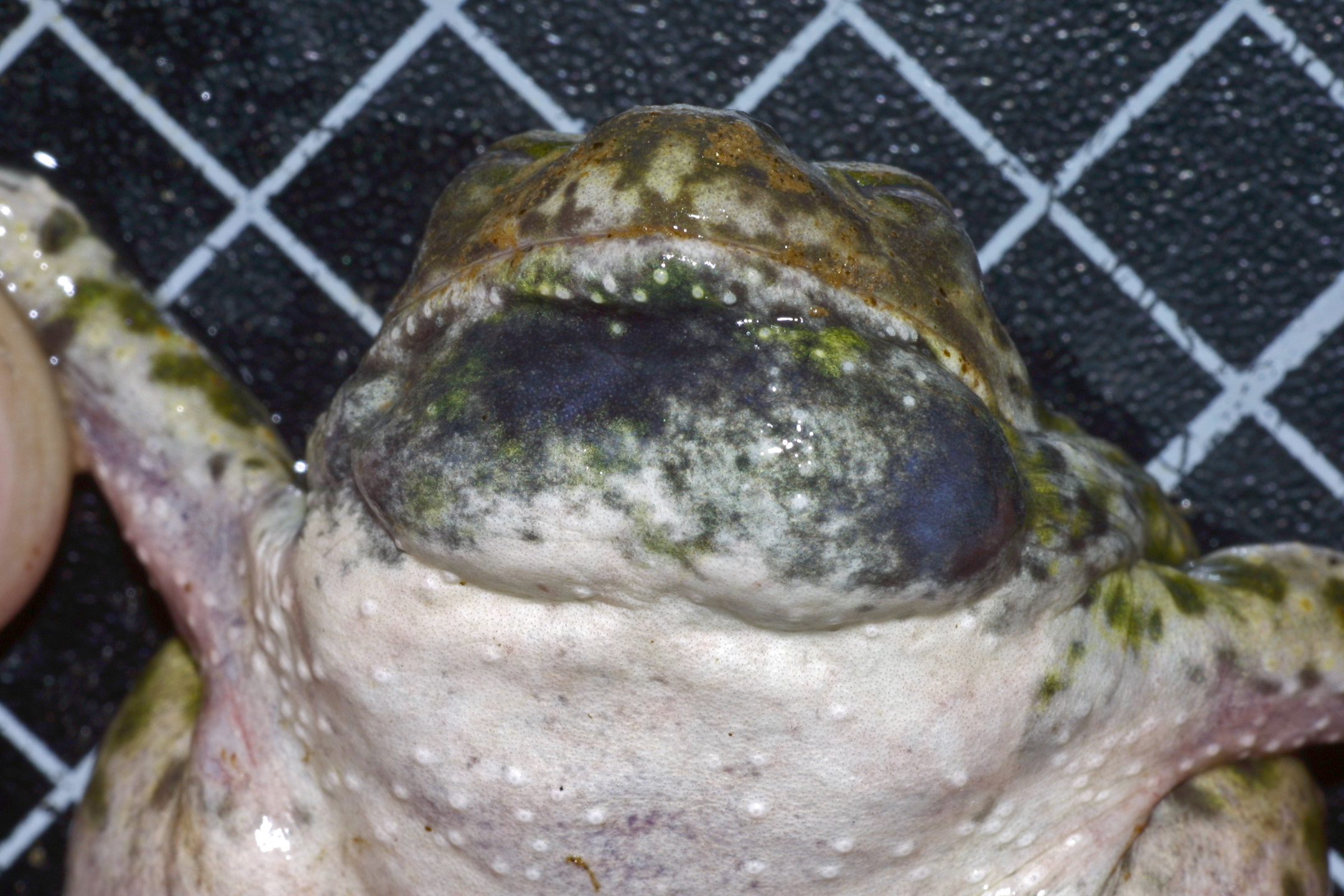

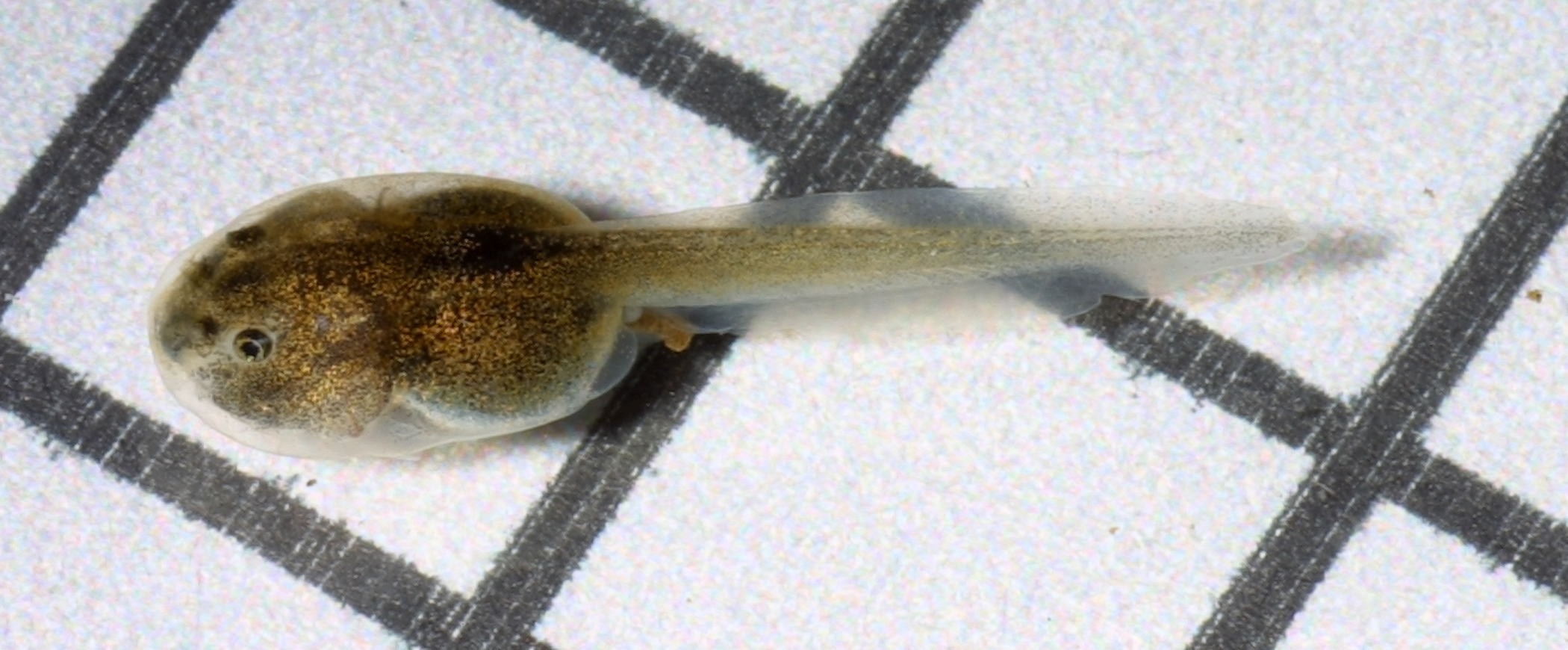

Mostly nocturnal, but can be heard calling during the day following winter and spring rain [5]. A medium-sized toad ranging in size from 3.7-6.2 cm (1.5-2.5 in) in length (Snout to vent length/SVL) [8,1]. Females are typically larger [5]. Adults have smooth gray-green to gray skin with small red or orange tipped vertebral tubercles and 4 irregular light colored stripes with dark blotches on the back and are whitish and unmarked below [9]. The characteristic glossy wedge shaped spade is found on the back of the hind feet [9]. They have short stout limbs and no visible parotid gland. The eyes are large with pale gold irises and vertical pupils [1]. Eggs hatch in 0.6 to 6 days after external fertilization depending on temperature [8]. Tadpoles transform in pools that last 30 days or more depending on food resources and temperature,but metamorphosis must be completed before pools dry [6]. Tadpoles are light gray to dark greenish brown in color, with a cream-colored underside and a transparent tail [9]. They can reach up to 3 inches long but usually transform at a smaller size to ensure metamorphosis before the pool dries [6]. Larval development is completed in approximately 58 days (range 30–79 days) and is closely tied with water ponding duration [8,1].

Diet and Foraging

The larvae are fast growing and have a tendency to hang vertically in the water to gulp air or feed on surface material [1]. They are carnivorous and have been observed preying on other species' tadpoles but also consume planktonic organisms and algae [5].

Dispersal

Juveniles leave the natal pool at night and disperse into the surrounding upland habitats [6]. However, little is known about their home range and about the distance between breeding pools and the site of the summer burrow [2]. There is no breeding during dry years due to a lack of environmental triggers to initiate breeding [7]. When males emerge, they congregate and float in pools to advertise or call for mates and establish a territory in pools with good breeding conditions [6,2].

Threats

Threatened by habitat destruction, habitat fragmentation and isolation, invasive species, climate change effects, altered fire regime, and alterations to the watershed [1]. Because western spadefoot toads depend upon ephemeral wetlands, alterations to the hydrology of an area will often dry-down pools before the life cycles of the species are completed, preventing reproduction and disrupting dispersal [1]. Invasive aquatic species like the American bullfrog, mosquito fish (Gambusia spp.) and crayfish (Order Decapoda) prey upon larvae and juvenile western spadefoot toads and out compete them for food resources in rapidly drying pools [7]. Climate change and prolonged drought effects threaten this species by changing its distribution and abundance across the range as air and water temperatures rise and hydroperiods shift in the seasonality and length of ponding may result in unsuitable conditions for completing its life cycle [10]. The western spadefoot toad is restricted in its distribution and it has a climate sensitive biphasic life history, therefore they may not be able to adjust their range to accommodate the available changes in the locations of suitable habitat due to habitat fragmentation [10].

Special Considerations:

Long-term population dynamics, survival rates, reproductive success, and dispersal rates are unknown [7,8]. Western spadefoot toads have been recorded in 11 of the 17 vernal pool regions described by Keeler-Wolf et al. in the California Manual of Vegetation [8,11]. The US Fish and Wildlife Service included the western spadefoot toad as a species of concern in the Draft Recovery Plan for Vernal Pool Ecosystems of California and Southern Oregon which provides guidelines for management, monitoring, and conservation actions for the species and the habitat [1]. The western spadefoot toad is also listed as a covered species in several regional Habitat Conservation Plans throughout its range in California [4].

Literature Sources

[1] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2004. Draft Recovery Plan for Vernal Pool Ecosystems of California and Southern Oregon. Portland, OR.

[2] Morey , S. 2000. Life History Account for Western Spadefoot Toad (Spea hammondii) In California Wildlife Habitat Relationships Systems, California Department of Fish and Wildlife. Originally published In Zeiner, D.C., W.F. Laudenslayer, Jr., K.E. Mayer, and M. White, eds. 1988-1990. California's Wildlife. Vol I-III. California Department of Fish and Game, Sacramento, California

[3] MSP-MOM. 2014. Management Strategic Plan Master Occurrence Matrix. San Diego, CA. Available: http://sdmmp.com/reports_and_products/Reports_Products_MainPage.aspx

[4] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2017. Species Profile for Western Spadefoot. Available: https://ecos.fws.gov/ecp0/profile/speciesProfile?spcode=D02Z#candidate Accessed: February 6, 2017.

[5] Morey, S. AmphibiaWeb. 2017. Spea hammondii Western Spadefoot. Available: http://amphibiaweb.org University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. Accessed: February 7, 2017.

[6] CaliforniaHerps; A Guide to the Amphibians and Reptiles of California, Western Spadefoot (Spea hammondii). 2017. Available: http://www.californiaherps.com/frogs/pages/s.hammondii.html. Accessed: February 7, 2017.

[7] Fisher R. N. and H.B. Saffer. 1996. The Decline of Amphibians in California's Great Central Valley. Conservation Biology, 10(5): 1387-1397.

[8] Morey, S. 1998. Pool Duration Influences Age and Body Mass at Metemorphosis in the Western Spadefoot Toad: Implications for Vernal Pool Conservation. ed. C.W. Witham, E.T. Bauder, D. Belk, W. Ferren and R. Ornduff, 86-91, Ecology, Conservation, and Management of Vernal Pool Ecosystems: Proceedings from a 1996 conference. California Native Plant Society, Sacramento, California.

[9] Stebbins, R. C. 2003. A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company.

[10] U.S. Department of Agriculture Climate Change Resource Center. Olson, D.H.; Saenz, D. 2013. Climate Change and Amphibians. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Climate Change Resource Center. Available: www.fs.usda.gov/ccrc/topics/wildlife/amphibians/ Accessed: February 7, 2017

[11] Sawyer, J. O., T. Keeler-Wolf, and J. Evens. 2009. Manual of California vegetation. California Native Plant Society Press.